The Come and Take It Flag: The Story of the Battle of Gonzales

As dawn broke on October 2, 1835, the small town of Gonzales, Texas found itself caught in a spectacular face-off against the might of Mexican military. The heart of this standoff? A tiny bronze cannon. But this was not about the cannon alone; it pulsated with an incontestable cry for freedom and defiance against oppression – one that would ultimately echo throughout history. It sparked a flame that led to the birth of a nation – the Lone Star State. This pivotal moment also gave rise to an enduring symbol known as the “Come and Take It Flag“. Just like David’s five smooth stones against Goliath’s mighty brute force served as an underdog’s powerful statement, so did this flag become a potent emblem for Texas that strongly resonates even today. Let’s delve into the past and uncover how Gonzales became ground zero in this high-stakes tug of war and the relevance of ‘Come and Take It’ in today’s world.

As dawn broke on October 2, 1835, the small town of Gonzales, Texas found itself caught in a spectacular face-off against the might of Mexican military. The heart of this standoff? A tiny bronze cannon. But this was not about the cannon alone; it pulsated with an incontestable cry for freedom and defiance against oppression – one that would ultimately echo throughout history. It sparked a flame that led to the birth of a nation – the Lone Star State. This pivotal moment also gave rise to an enduring symbol known as the “Come and Take It Flag“. Just like David’s five smooth stones against Goliath’s mighty brute force served as an underdog’s powerful statement, so did this flag become a potent emblem for Texas that strongly resonates even today. Let’s delve into the past and uncover how Gonzales became ground zero in this high-stakes tug of war and the relevance of ‘Come and Take It’ in today’s world.

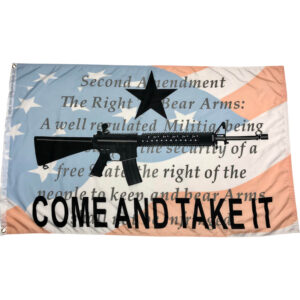

The “Come and Take It” flag was first used in defiance by Spartan King Leonidas I at the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC. The slogan was also used during the American Revolutionary War, but its most famous use was during the Battle of Gonzales in October 1835 when Texans successfully resisted Mexican forces who had orders to seize a loaned cannon. Caroline Zumwalt and Eveline DeWitt made a flag containing the phrase “come and take it” alongside a representation of the cannon. Today, it remains a symbol of Texan pride, rebellion, and resistance against encroaching authority.

Origins of the Come and Take It Flag

The famous “Come and Take It” flag has been a symbol of Texas pride since the Battle of Gonzales nearly 200 years ago, but where did this flag originate from? The origins can be traced back to Ancient Greece and the story of Spartan King Leonidas I at the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC.

The famous “Come and Take It” flag has been a symbol of Texas pride since the Battle of Gonzales nearly 200 years ago, but where did this flag originate from? The origins can be traced back to Ancient Greece and the story of Spartan King Leonidas I at the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC.

In many ways, the story of Leonidas I has parallels with the events that transpired during the Texas Revolution. Both stories are centered around a smaller group fighting against a larger, more powerful force. Similarly to how Leonidas’ Spartans were vastly outnumbered, a small group of Texans stood up against the Mexican army who possessed overwhelming military capabilities.

During the Battle of Thermopylae, King Xerxes had demanded that Leonidas and his 300 soldiers surrender their weapons. Leonidas famously replied: “Come and take them.” This defiant answer illustrated his refusal to give in to his foe’s demands. The phrase became iconic and has been reused in multiple historical contexts, including later conflicts in American history.

The connection between ancient Greek history and the events of the Texas Revolution is not mere coincidence. Many people during this time period were heavily influenced by classical education, which meant that they had studied authors such as Homer or Herodotus. As a result, references to ancient Greece would have been commonplace in intellectual conversation.

So how does Leonidas’ phrase make its way across centuries from ancient Greece to Texas?

Spartan King Leonidas to the Battle of Gonzales

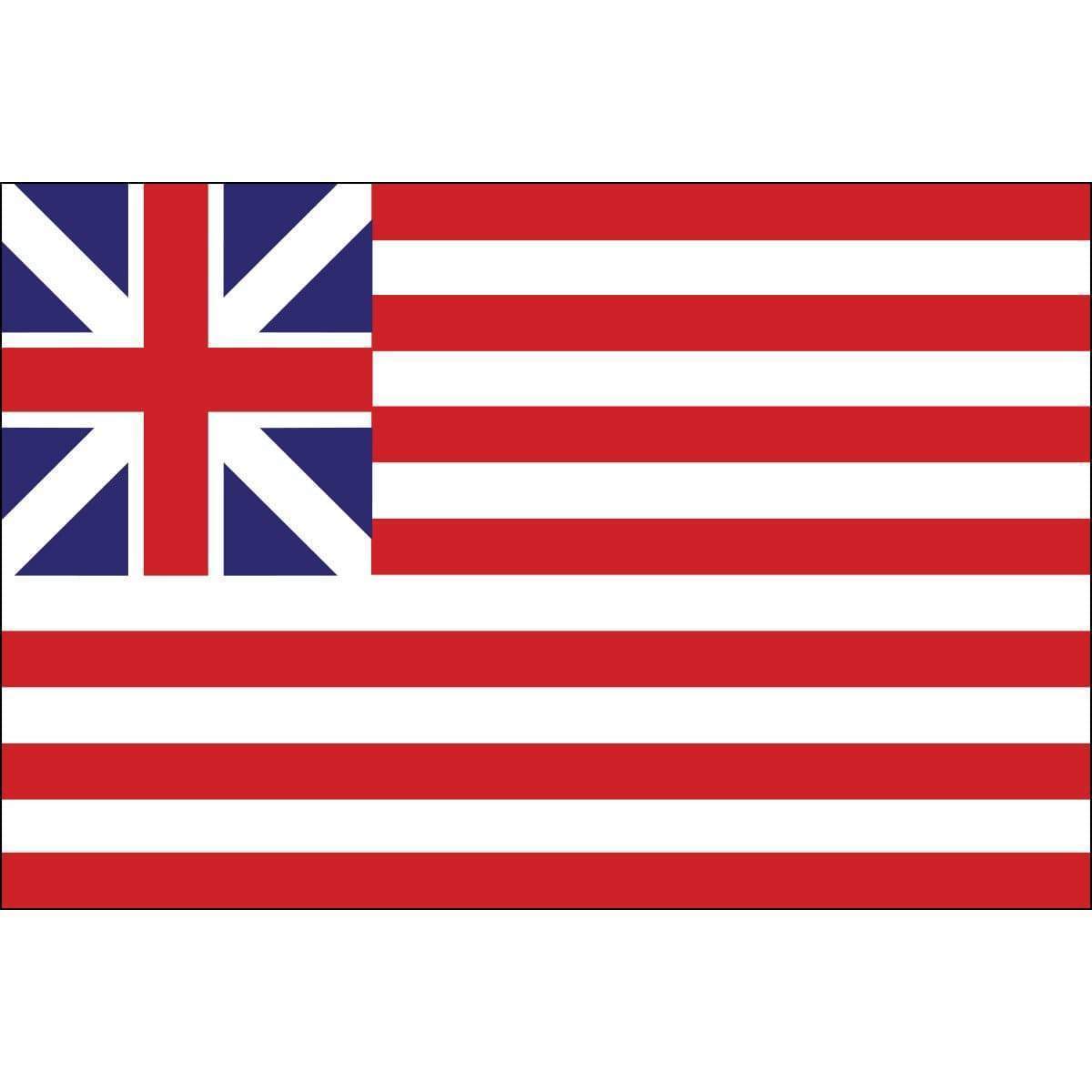

Fast forward several centuries after the Battle of Thermopylae, and we find ourselves in 1778 during the American Revolutionary War at Fort Morris in Georgia. There, Colonel John McIntosh led the American army against British forces. When the British demanded that he surrender, Colonel McIntosh used a variation of Leonidas’ phrase and replied: “As to surrendering the fort, receive this laconic reply: COME AND TAKE IT!” The British backed off because they lacked the intelligence regarding other American contingents in the area.

Like Leonidas before him, Colonel John McIntosh refused to give in to the demands of his enemy. And similarly to how Leonidas’ phrase persisted through time, it was this event at Fort Morris that would result in an iconic slogan being passed down through generations.

In 1835, Texans borrowed this phrase in response to Mexican attempts to seize a cannon in Gonzales. At the Battle of Gonzales, Caroline Zumwalt and Eveline DeWitt sewed a flag containing the word “Come” alongside a picture of a cannon and added the words “and Take It”. This flag became an important symbol during Texas’ fight for independence.

Some scholars have debated whether the phrase “Come and Take It” was meant as a threat or not. Some argue that it could be read as simply inviting the Mexican army to come and take their one obsolete piece of artillery. However, most historians agree that the phrase reflects Texas’s unyielding spirit and desire for independence from Mexico.

As we’ve seen, the “Come and Take It” slogan has its roots firmly planted in ancient Greece, but its true legacy is undoubtedly linked to its use during formative moments in American history such as the Battle of Gonzales.

- During the Battle of Gonzales, Texans resisted Mexican forces, depicting an event that marked the beginning of Texas’s War for Independence from Mexico.

- Despite its local origin, the phrase has been borrowed from historical events dating back to 480 BC, underlining its deep-rooted tradition in historical resistance movements.

Cultural and Historical Context

To fully understand the significance of the Come and Take It Flag, we must examine the cultural and historical context that surrounds it. The flag represents an important part of Texas history, but also reflects a broader theme of resistance against tyranny and oppression.

To fully understand the significance of the Come and Take It Flag, we must examine the cultural and historical context that surrounds it. The flag represents an important part of Texas history, but also reflects a broader theme of resistance against tyranny and oppression.

As Texans voted in favor of statehood, they hoped to be annexed by the United States. After being rejected, they instead formed the Republic of Texas as a Plan B. While most revolutionaries were not native Texans, they shared a common bond in their desire for independence from oppressive rule.

Moreover, Texas was a slaveholder republic. The Republic of Texas constitution was explicitly written to establish, maintain, and preserve slavery into perpetuity. This fact is essential because it shows that the Come and Take It Flag represents not only freedom from Spanish/Mexican oppression but also the right to own slaves.

This brings us to another critical aspect of contextualizing the flag’s origin: Native American history in Texas. Historians have noted that more emphasis needs to be placed on Native American tribes’ contributions and experiences in shaping Texas history, particularly that of the Comanche tribe. As we celebrate and honor our own pride for Texan independence, we must acknowledge that this land belonged to people long before us.

Finally, it’s worth considering the role of politics in shaping Texas history curriculum. The State Board of Education oversees setting the curriculum specific to teaching Texas history. They are elected positions subject to political influence. Given that those positions get filled through popular demand rather than qualifications or expertise, political agendas can impact what students learn in school.

To illustrate this point more concretely: in 2010, there was significant push-back against updating textbooks with references to non-Christian religions or relations with Mexico on topics like immigration. The vote determined what went into textbooks used all over the country and where other states followed suit.

With this contextual backdrop, let’s now examine the Battle of Gonzales and how it represents a defining moment in Texan history.

- Understanding the cultural and historical context surrounding the Come and Take It Flag is crucial to fully grasp its significance. The flag represents resistance against oppression, including both Spanish/Mexican rule and the right to own slaves. In exploring the Battle of Gonzales, we must also acknowledge Native American contributions to Texas history and consider how politics can impact what students learn about their state’s past.

The Battle of Gonzales: An In-depth Analysis

The Battle of Gonzales is a critical event in Texas’s fight for independence. What set it apart from other early confrontations was that it was the only battle fought under the “Come and Take It” banner, which Texans used to symbolize their determination to resist tyranny.

The Mexican Occupation and Rebel Response

Mexican government officials ordered a small cannon to be confiscated from Texan citizens living in Gonzales. In response to that order, about 150 Texans gathered to challenge the action. Gunnery Sergeant Horace Eggleston allegedly fashioned a flag with a likeness of the cannon, along with the words “Come and Take It!”.

Mexican government officials ordered a small cannon to be confiscated from Texan citizens living in Gonzales. In response to that order, about 150 Texans gathered to challenge the action. Gunnery Sergeant Horace Eggleston allegedly fashioned a flag with a likeness of the cannon, along with the words “Come and Take It!”.

Ultimately, the Texans successfully resisted Mexican forces and kept their cannon. However, this victory marked one of several early rebellions that eventually escalated into full-blown war.

Some argue that Texas’s struggle for independence was unnecessary and immoral, arguing that it was fueled by support for preserving an inhumane institution- slavery. In essence, such people point out that even if Mexico possessed all the potential markers of tyranny, including authoritarianism and corruption- were those reasons good enough to justify fighting and shedding blood?

Those counterarguments are valid because motivations for supporting Texan independence can be complex or murky at best. But historical hindsight must also take into account why many Americans decided to move Westward during manifest destiny. By default, America’s leaders would have wanted those Western lands to become US territories rather than remain under foreign rule.

This fact alone makes it difficult to argue that fighting for Texan independence was entirely unjustified or unnecessary- even if we recognize all its moral failings today.

Nonetheless, regardless of where we stand on the justness of the original motivations for fighting, we must agree that the Battle of Gonzales and the flag that represented it continue to hold significant meaning in modern Texas.

The Mexican Occupation and Rebel Response

The Mexican government initially believed it could easily quell the rebellion in Texas. However, they soon realized that it would not be an easy victory. When Governor Martínez de Castro declared a state of martial law in Texas, revolutionary forces decided to take action. They seized control of Gonzales’ single cannon that was being used to protect the town against Native American raids. After the cannon had been taken by Texans, the Mexican troops demanded its return, but the “Come and Take It” flag presented the revolutionaries’ defiant answer.

In response to their refusal to return the cannon, over 100 Mexican dragoons under Lieutenant Francisco Castañeda were sent to Gonzales on October 1st, 1835. The events leading up to the battle varied significantly depending on who tells them. Some blamed drunk soldiers for triggering the conflict, while others reported that Captain Robert M. Coleman intentionally provoked the Mexicans. Regardless of how it began, after a brief skirmish at Gonzales on October 2nd, 1835, all but one of the Mexican soldiers retreated back to San Antonio.

This defiance by Texas kicked off a chain of events leading to war and ultimately paved the way for Texas becoming its own independent state. Furthermore, it heightened national interest in America’s southwestern frontier and helped push America toward a war with Mexico and ultimately land expansion across North America.

However, many historians argue that although this battle is often considered as where Texans took up arms against Mexico’s autocratic government; in reality it was a stand-off between settlers and civil officials over what role or authority each respective group had over governance within Texas. Additionally, some contend that stories like those from Gonzales were expanded upon or even fabricated over time because Texans needed them as rallying points.

Despite disagreements about the true origins of the battle, it is clear that something significant happened on that day in Gonzales. It was a rallying point for Texans who wanted to pursue their independence and a decisive victory against an overzealous Mexican regime.

Significance of the Come and Take It Flag

The “Come and Take It” flag has developed into a symbol of Texas’ spirit of rebellion. Initially, it was nothing more than a piece of white cloth with black lettering designed to taunt the Mexicans that claimed ownership over the small and outdated cannonbrought to Texas by Spanish armies during earlier time. The flag’s popularity increased when Texas began its fight for independence from Mexico.

The flag embodies Texas’ resistance to outsiders who try to impose their will on its citizens. In many ways, it is an expression of Texan identity. To this day, variations of the “Come and Take It” flag can be seen throughout Texas in various forms, from bumper stickers to t-shirts, posters, and even tattoos.

During the peaceful protest movements of the 1960s and ’70s, several Chicano activists changed the decoration around the cannon illustration on flags. Instead of emphasizing the destruction brought about by war, they chose instead to rally behind broad themes like anti-imperialism or cultural pride under keywords like “Viva Tejas” or “Chicano Power.” This adaptation highlighted a new wave of rebelliousness among Hispanic youth in Texas.

However, some critics have different opinions and have pointed out that while “Come and Take It” may seem like a proud rallying cry for Texans against government surveillance or federal politics; for others it is hard not to see it as coded language against racial groups who constitute a large part of modern-day Texan history such as Black Americans or Indigenous Peoples.

Imagine two siblings both getting scolded for playing with something they shouldn’t. One sibling grows up and uses their punishment as a rallying point to reject authority and embrace rebellion, while the other sibling tries to forget the event or move past it. While both siblings were punished, one chose to own it as part of their identity.

The “Come and Take It” flag represents a rebellious spirit that dates back nearly 200 years. Regardless of whether people agree on its interpretation, there’s no denying that the flag is woven into Texas’ story as part of its resistance against outside power and a big part of its self-identity.

Embodying the Spirit of Independence

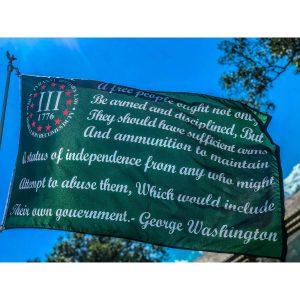

The Come and Take It flag embodies the spirit of rebellion, defiance, and independence that characterized Texans during the early years of their independence. This flag, with its simple message of resistance, has become a symbol of liberty and self-determination for many Texans. The phrase “Come and Take It” sends a clear message to those who would seek to limit the freedom of others: Texans will not back down in the face of oppression.

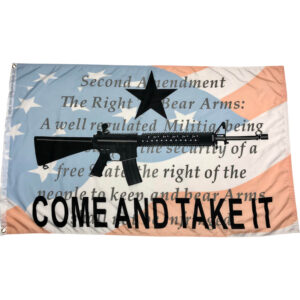

Anecdotal evidence shows how powerful this symbol can be. For example, in 2013, Texas gun enthusiasts used variations of the Come and Take It flag to protest new gun control laws proposed after the Sandy Hook shooting. They saw the right to bear arms as crucially important for their own safety and the protection of their families. Using the flag as a rallying cry helped bring attention to their cause and inspired others to join them.

Anecdotal evidence shows how powerful this symbol can be. For example, in 2013, Texas gun enthusiasts used variations of the Come and Take It flag to protest new gun control laws proposed after the Sandy Hook shooting. They saw the right to bear arms as crucially important for their own safety and the protection of their families. Using the flag as a rallying cry helped bring attention to their cause and inspired others to join them.

Furthermore, examples show that Texas musicians have also embraced the spirit of independence and uses the flag as an emblem of defiance against government overreach. One such musician is Steve Earle, who used images from Gonzales on his album cover “Jerusalem”.

At its core, the Come and Take It flag represents not only Texan values but universal human values of democracy and liberty. Its message resonates with people worldwide who yearn for freedom.

In fact, that is why this flag still remains relevant nearly two centuries after it was first waved in battle – because it speaks to our innate desire for self-determination. We all want to be free from tyranny and oppression; we all want to chart our own course in life. The Come and Take It flag captures these ideals in a simple yet powerful manner.

Moreover, some might argue that using rebellious symbols like the Come and Take it Flag could lead to division in society or even incite violence. However, history has shown the power of protest and civil disobedience, which can lead to positive change. The flag is not a call for violence or anarchy, but rather a symbol of resistance against oppressive forces.

It’s like Mahatma Gandhi’s Salt March in India, which was a non-violent protest against the British salt tax. These movements sought to change unjust laws and systems, and their methods were rooted in principles of justice and human rights.

Now that we have established what the Come and Take It Flag represents, let’s examine its legacy over the years.

Legacy of the Come and Take It Flag

The legacy of the Come and Take It flag extends far beyond its use during the Texas Revolution. This flag has become an enduring symbol for those who value personal freedom and individual liberties; it embodies a spirit of resistance that transcends national boundaries.

Replicas of the original flag can be seen across Texas, as well as in museums and private collections around the world. The flag has also been adapted for various purposes – from firearms advertisements to political campaigns – but each use retains some connection with its original meaning.

One example of how this symbol resurfaced is with Ted Nugent’s song “Come and Take It” from his 2022 album Detroit Muscle. The song celebrates American values of liberty and individualism, which are embodied in this resilient flag.

Moreover, today, many Texans still associate the flag with their state’s rugged independence and colorful history – something unique from other states’ identities. Even though it may represent different things to different people, one thing is clear: The Come And Take It Flag remains an important part of Texas’ heritage.

In recent times, some have criticized the use of Confederate symbols like the flag, arguing that they represent a legacy of racism and oppression. But the Come and Take It Flag, while rooted in a struggle against colonialism, represents an ideal that is universal and ever-relevant.

In recent times, some have criticized the use of Confederate symbols like the flag, arguing that they represent a legacy of racism and oppression. But the Come and Take It Flag, while rooted in a struggle against colonialism, represents an ideal that is universal and ever-relevant.

As long as there are those who believe in freedom and resist tyranny, this flag will continue to be a powerful symbol of hope. Its legacy will be passed down to new generations, inspiring them to stand up for their rights and fight for justice wherever it may be threatened.

Of course, some may argue that the flag is just another emblem of Texan exceptionalism. However, it represents more than that. It acknowledges that fight for independence from larger forces who seek only to exert power over other people without regard for their human rights.

In that sense, it’s similar to other independence movements around the world – from India’s struggle against colonialism to the American Revolution itself – which sought to secure freedom and sovereignty for their people.

Replicas, Adaptations, and Current Usage

The legendary Come and Take It flag has become ingrained in Texan culture, symbolizing the state’s unwavering independence and heritage. As such, it is not surprising that numerous replicas and adaptations of the original flag have been created to commemorate or adapt the design to different contexts.

Several replicas of the Come and Take It flag can be seen across Texas, including the San Jacinto Monument, where a massive granite monument marks the location of Texas’ defining battle. In Gonzales, you can find an annual Come and Take It Festival recreating the historic events surrounding the flag’s creation. Similarly, variations of the Come and Take It motif have been used for merchandise items such as t-shirts, hats, mugs, tattoos, etc.

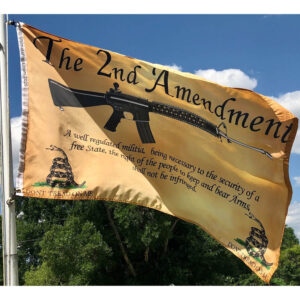

Beyond simple reproductions, artists have also sought to adapt the Come and Take It design for modern audiences. The flag has been modified to include other firearms such as AR-15 rifles rather than just a cannon. Some versions incorporate humorous references to pop culture such as substituting the cannon with Baby Yoda from Star Wars: The Mandalorian or Boba Fett’s helmet.

Moreover, artists have taken inspiration from the Come and Take It flag in creating new designs for slogans that represent contemporary political sentiments. For example, “Come and Take It Back,” which advocates taking back power from those who don’t serve citizens’ interests.

While many consider these adaptations as a form of respect towards Texan cultural history, some argue they dilute real understanding of the original symbol’s deep historical significance. Critics claim these changes reflect personal views on gun rights or current technologies without truly contributing any meaningful insight into Texas history.

However, whether or not one believes in these interpretations are besides the point; it is still essential to recognize how relevant debates around gun rights and self-governance were and still are in Texas.

You could compare the changes made to Come and Take It flags to remakes or adaptations of classic literary works or movies. Some remakes capture the essence of the original while others add nothing new. Regardless, each remake has its own strengths and weaknesses.

The Come and Take It flag has come a long way since its creation, but it still remains an iconic piece of Texas visual culture. It will inevitably continue to inspire artists and designers as it embodies a spirit of defiance, independence, and resilience that endures in Texas’ history and aspirations.

Bonus – Flags are tools of Expression and Unity!

Bonus – Flags are tools of Expression and Unity!

The Gonzales flag has become a symbol of pride for Texans who value their right to bear arms. But how did it come about, and why is it still relevant today? The origins of the flag date back to the

The Gonzales flag has become a symbol of pride for Texans who value their right to bear arms. But how did it come about, and why is it still relevant today? The origins of the flag date back to the

The

The

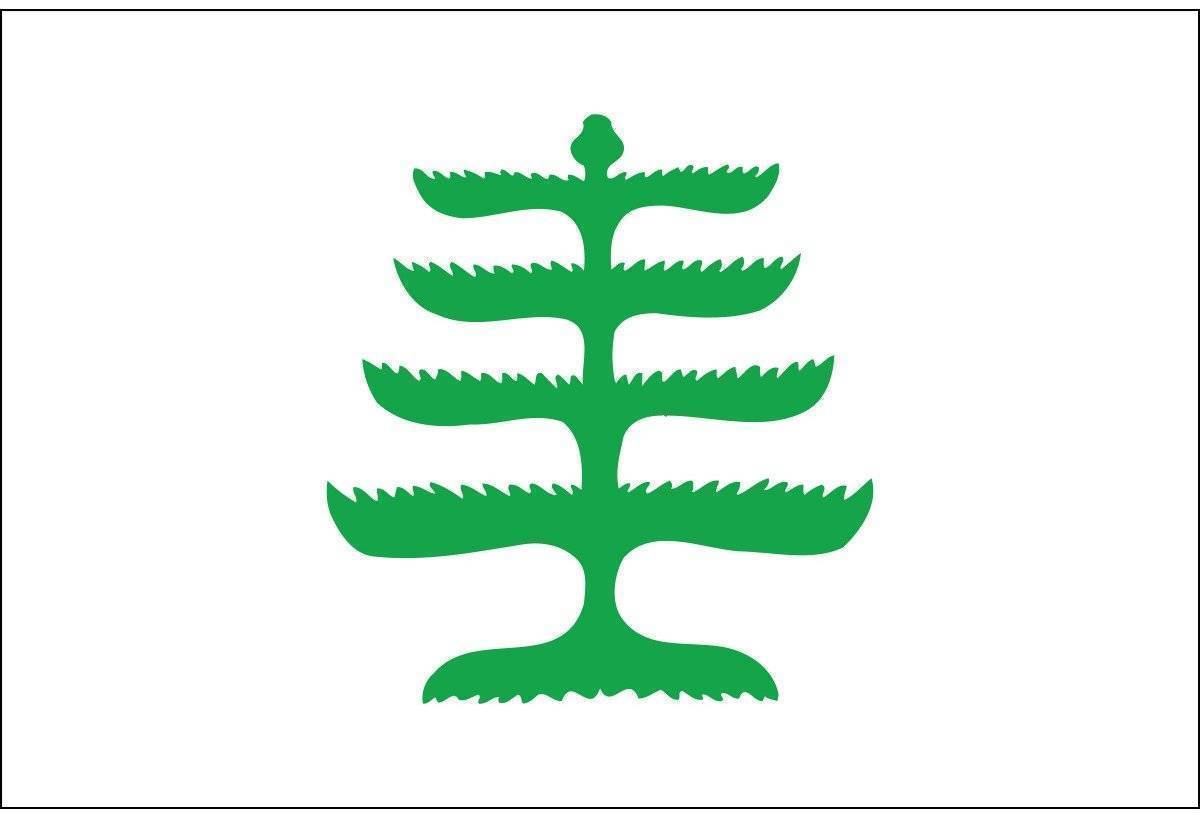

The rattlesnake served as a powerful symbol in America during the late 18th-century. The use of this unique and deadly creature on the Gadsden flag was fitting for the time, considering the sentiments of a young nation fighting against its former rulers. This animal represented several qualities that were important to the American Revolutionaries.

The rattlesnake served as a powerful symbol in America during the late 18th-century. The use of this unique and deadly creature on the Gadsden flag was fitting for the time, considering the sentiments of a young nation fighting against its former rulers. This animal represented several qualities that were important to the American Revolutionaries.