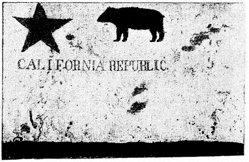

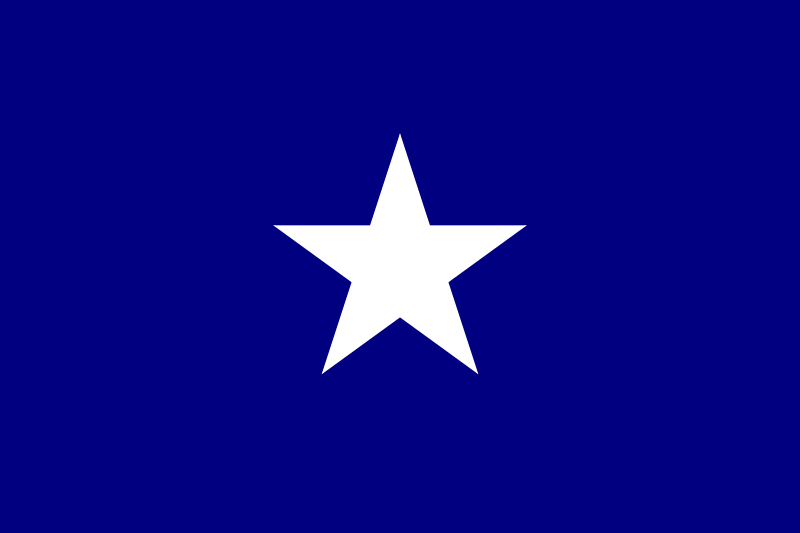

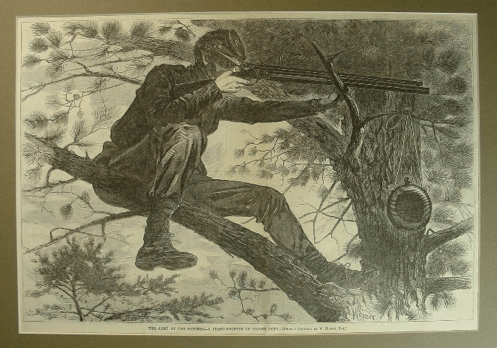

It is always inspiring to hear stories of about the courage of soldiers during battle. George Bravard was a flag bearer serving the 1st Texas infantry regiment during the Civil War.

Confederate Colonel Philip A. Work, the commander of this famous “Ragged Old First,” pointed to a rise in the distance and said,

“Follow the Lone Star Flag to the top of the mountain.”

At that moment a Union cannon shell landed in their midst. Branard vowed he would wave his flag over the gun that fired that shot. He set out toward the mountain with his fellow Texans as shells fell all around him. Nearly a third of the men were killed or wounded during the advance, but Bravard kept on going.

He passed well beyond the rest of the men. The regiment left behind shouted and urged him to turn back. His death was near certain, but Branard was on a mission. He had made a vow. All of a sudden they heard this command coming from the Federal lines,

“Don’t shoot that man! He is too brave to kill!”

For a brief time, all gunfire stopped. But then a shell suddenly exploded at Branard’s feet. A fragment struck him in the forehead, gashing his face, blinding his left eye and destroying hearing in his left ear. The blast ripped the Lone Star colors from his hand. He managed to recover it and clutched it closely again. As he struggled to move forward, he passed out. Fellow soldiers thought he was dead and carried him off the field.

But that was not the end of Bravard, as he did survive. Amazingly, after only one day of recovery, the brave color bearer was back on duty. He was wounded again in following battles, but he never quit.

He proudly carried that Lone Star flag and wore his uniform until the very end of the war.

George Branard, Flag bearer of 1st Texas

![]()

Thanks for reading. Please share our posts with your friends and family so they too can learn more about Southern Heritage and History.

Brought to you by: Ultimate Flags