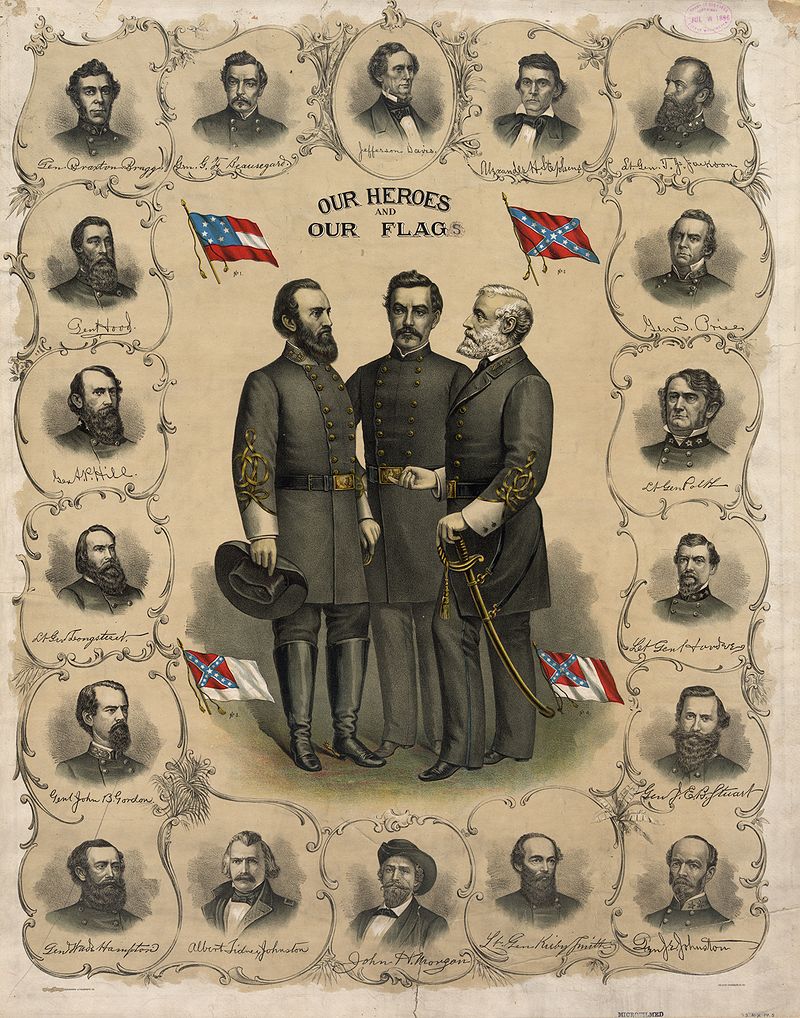

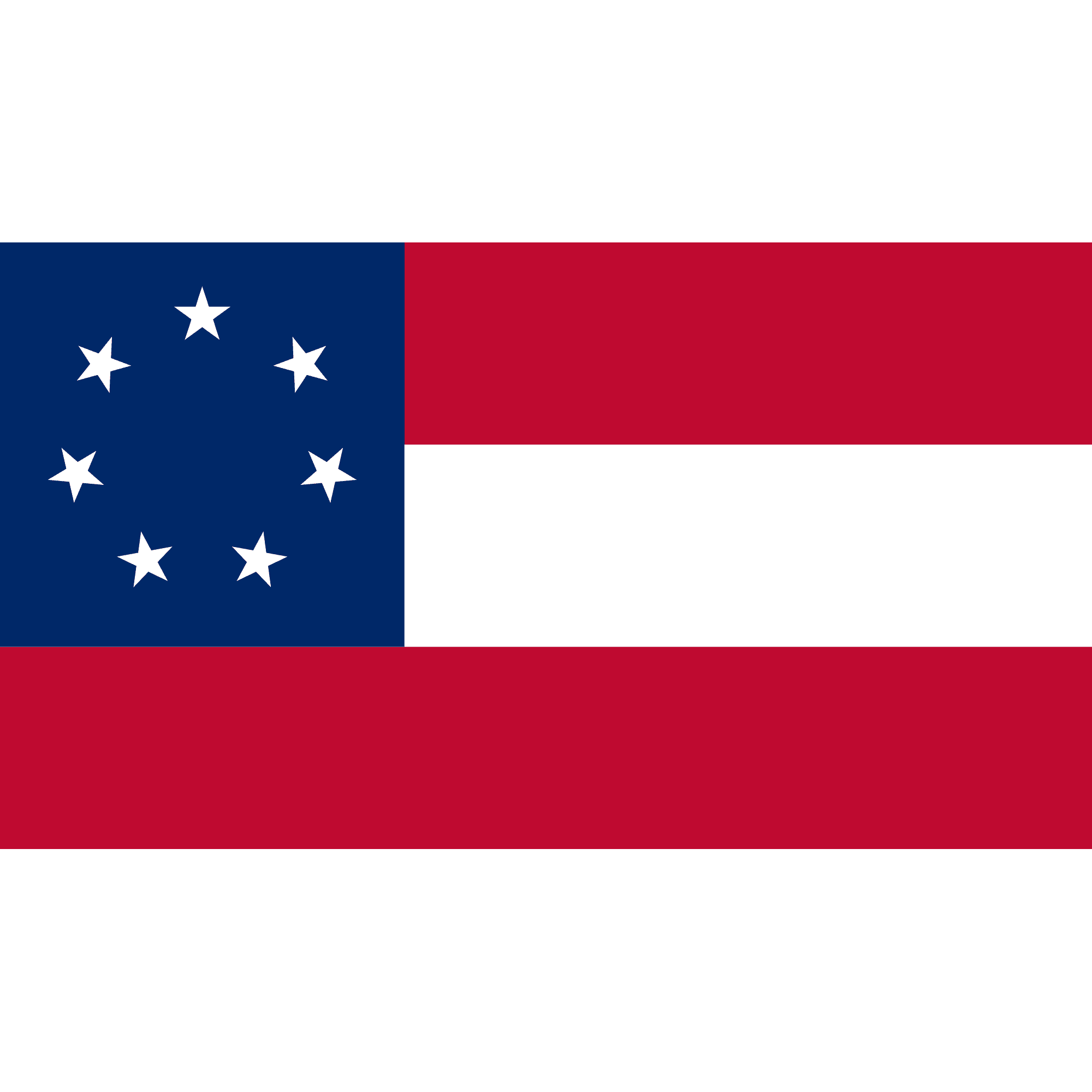

After its birth the First National Flag of the Confederacy became known as the Stars and Bars. Now some may raise their eyebrows, believing that term applies to the Confederate Battle Flag. I don’t want to upset anyone, but the Battle Flag was known to soldiers as the Southern Cross. (I’ve written about its tale in an article on the battle flag, where you can read the words of the Confederate veterans themselves.)

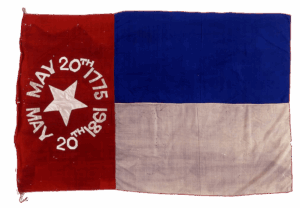

7-Star First National Flag of the Confederate States of America

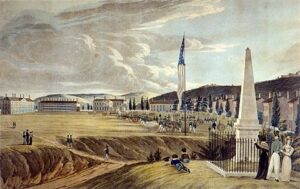

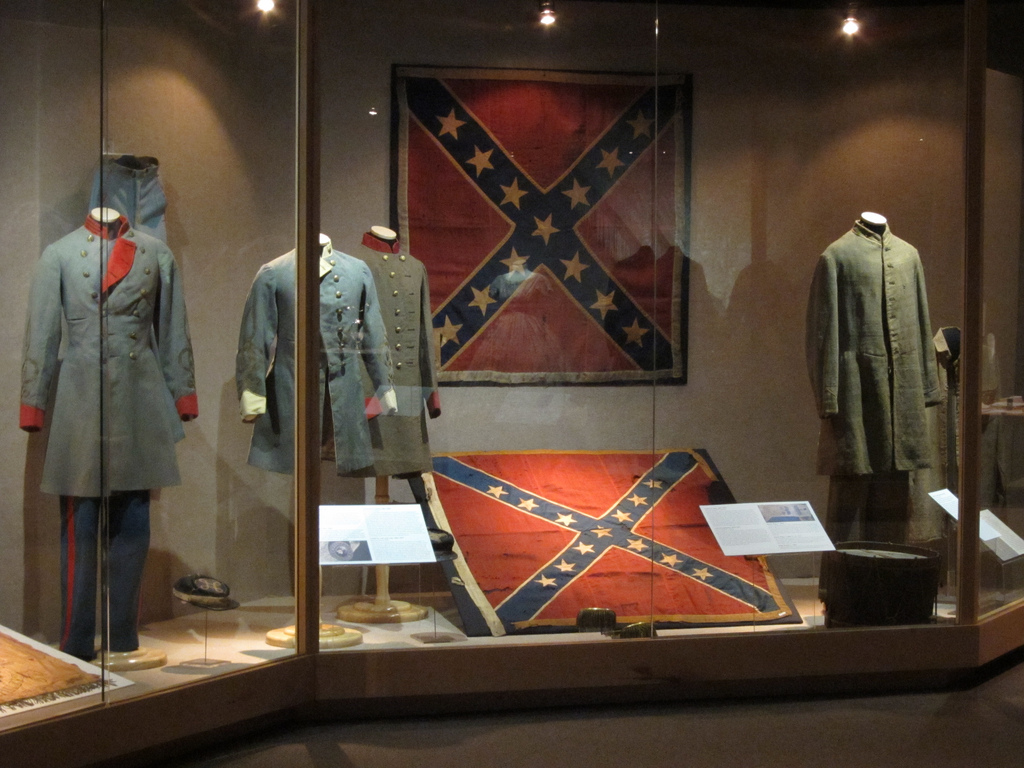

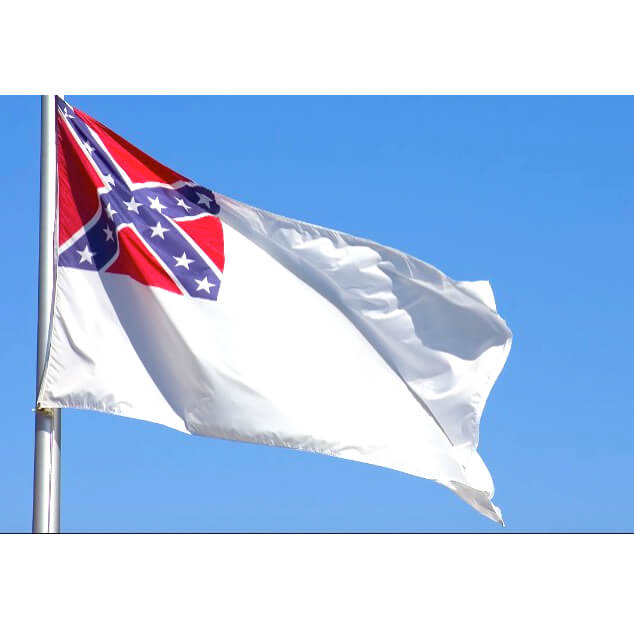

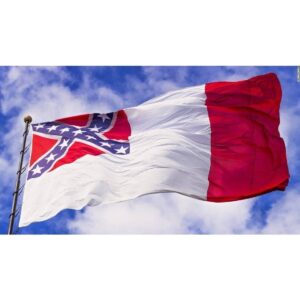

We say “First National” because this was the first of three official national flags of the Confederate States of America. Its design was presented to the provisional congress of the Confederate States by the flag committee on March 4, 1861 – about five weeks before Ft. Sumter was fired on (that is Ft. Sumter in the first photo of this article, the Stars and Bars flying). The records show no recorded vote: it was adopted by just writing it into the congressional journal.

There are two common stories about who designed this flag, and a lot of folks have debated and fussed over which is right. The disagreement has never reached the level of the Hatfields and McCoys feud, but there have been some raised voices, and we can a black eye or two.

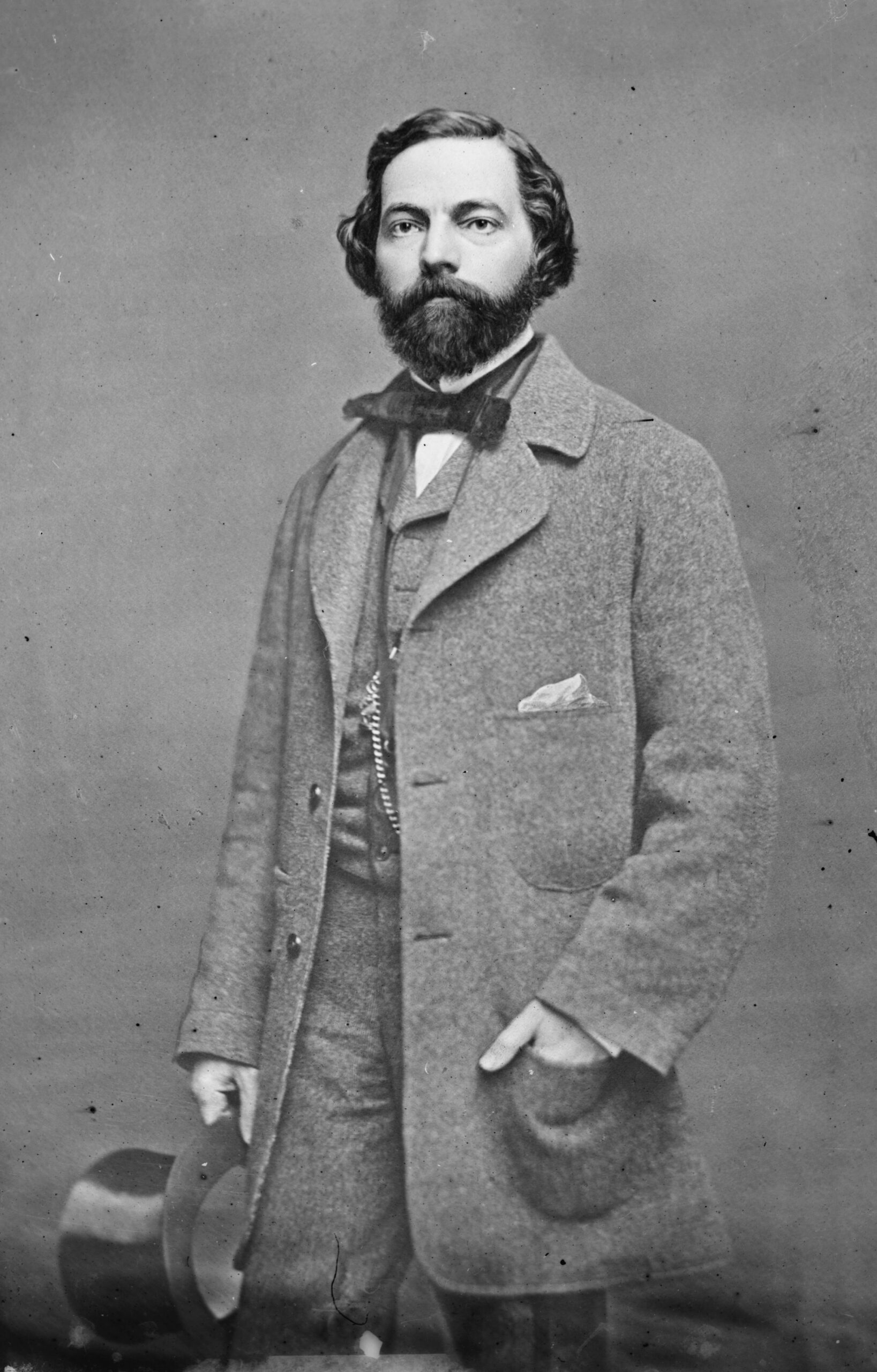

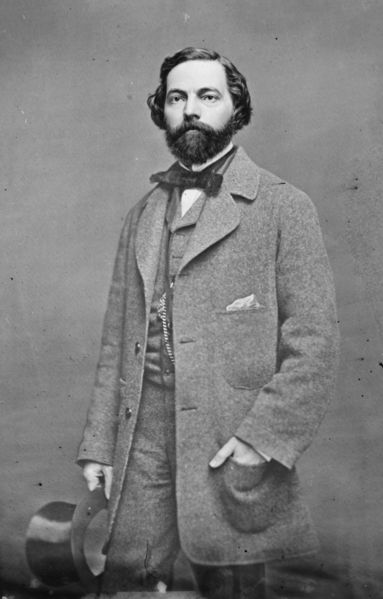

Nicola Marschall, Self-Portrait of 1881

One of these tales says that the flag was drawn by Nicola Marschall, a successful artist of the era. In fact, Marschall painted a portrait of President Jefferson Davis himself. Marschall joined the Confederate army, rose to be a Lieutenant in an engineering regiment, and chief draftsman for various maps and fortifications during the war.

Marschall wrote that he did three different designs for the flag, one of which resulted in the Stars and Bars. Details are written up in an interview he did for a 1917 newspaper article. One can read this information in many works from university and government sources (particularly Alabama, where Marschall lived at the outbreak of the war).

One might be convinced by this scholarly work. Of course, the sentences and wording do seem to repeat a great deal, as if these writings were going along in a series, one copying another. Marschall is commonly described as a German-American or a Prussian, and it is often stated that he was inspired by the Austrian flag. Well, the Austrian flag had three bars, red on top and bottom and white in the middle. Makes for good story-telling, but as evidence it has discard value only.

Another story revolves around a tombstone in Henderson, North Carolina, marking the burial spot of Orren Randolph Smith. This stone has an inscription, “Designer of the Stars and Bars.” Smith claimed (in his later years) that he had designed the original national flag of the Confederate States of America.

Let’s take a look at what the wartime records show.

The National Archives has the flags book of the Confederate Congress, all the letters and documentation, and many of the design submissions for the various Confederate national flags during the war. While not everyone provided a name on their proposal, all those that did are in the records.

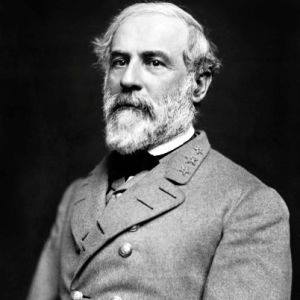

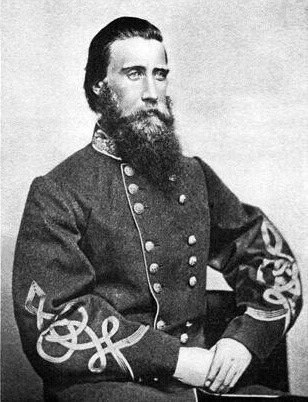

Neither Smith’s nor Marschall’s name appear anywhere in the book, nor in the notations of the Confederate Committee on Flag & Seal. On the contrary, the chairman of the Flag Committee, William Porcher Miles, was very clear on this matter. He wrote that the flag design presented to the Confederate States Provisional Congress was not chosen from any of the submitted designs, but was created by the flag committee itself.

William Porcher Miles

None of the period newspapers of the time (March, 1811) ever stated anyone as being the designer. If there had been a name circulated at all, it most certainly would have made its way into the press. And I think we can count on the fact that the reporters would have been looking for one (especially that of a prominent person such as Marschall). Those newspaper accounts that mention the details of how the flag came are unanimous that it was created by the flag committee.

In truth, design proposals had flooded in from all over, including many from the North. With so many designs there were bound to be some that had one or more similarities to the final product, bringing about situations where various people might claim they designed the flag.

In fact, we know of such a design in the records of the Committee on Flag and Seal of the Confederate States Congress, submitted by someone from South Carolina. That design resembles the First National, with some differences. The stars are on a red field, instead of a blue field. There are three bars, but instead of top and bottom bars of red, they are blue.

So the best evidence is that the Confederate Congress Committee on Flag and Seal came up with the design, as Miles reported. But some individuals presented designs that were close enough to the final result that they could have believed they were the actual designer. Any number of folks may have thought this was the case, but never made a case for it. And we can be pretty sure others than Marschall and Smith spoke up, but we just don’t have a record of it. (Bear in mind that both Nicola Marschall of Alabama and Orren R. Smith of North Carolina made their claims as the designers after the war was over – in the case of Smith way after the war.)

On the other hand, who am I to get in the way of a good feud?

Thanks for reading. Please share our posts with your friends and family so they too can learn more about Southern Heritage and History.

Brought to you by: Ultimate Flags