Exploring the History of the Confederate Flag: Its Origins and Significance

In 1861, with the impending vigor of the Civil War, a flag was born – a banner that soon became infamous for its hidden layers of symbolism and controversy. This flag, the Confederate Flag, is more than just a brilliant canvas of red, blue, and white stars. It is much like an iceberg submerged in deep waters; what meets the eye is only a fraction of its layered truth. Embracing its narrative requires diving into murky depths to discover the unseen magnitude beneath. A tale buzzing with conflict, heritage and mythology awaits us as we embark on this historical expedition to uncover the origins and significance of the Confederate Flag.

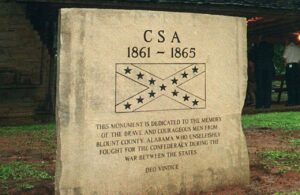

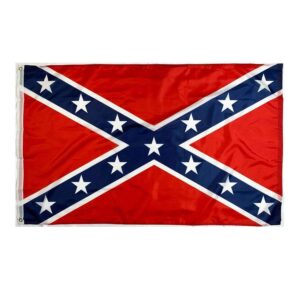

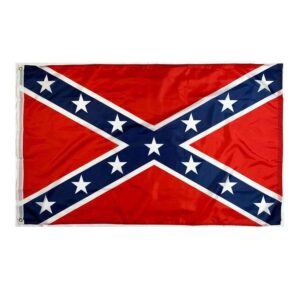

The Confederate flag has a complex and controversial history. It was a symbol used by the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War, representing Southern pride, and states’ rights. In modern times, it has been adopted by some as a symbol of Southern heritage and rebellion, while others view it as a symbol of racism and hatred. Despite not being an official national flag, its use and display remain a contentious issue in the United States.

Evolution of the Confederate Flag Designs

The history of the Confederate flag is complex and controversial. It has gone through three major design changes during its brief existence as the symbol of the Confederate States of America. These changes reflect not only the political and social changes within the Confederacy but also how flags themselves can be used to convey meaning and identity.

The history of the Confederate flag is complex and controversial. It has gone through three major design changes during its brief existence as the symbol of the Confederate States of America. These changes reflect not only the political and social changes within the Confederacy but also how flags themselves can be used to convey meaning and identity.

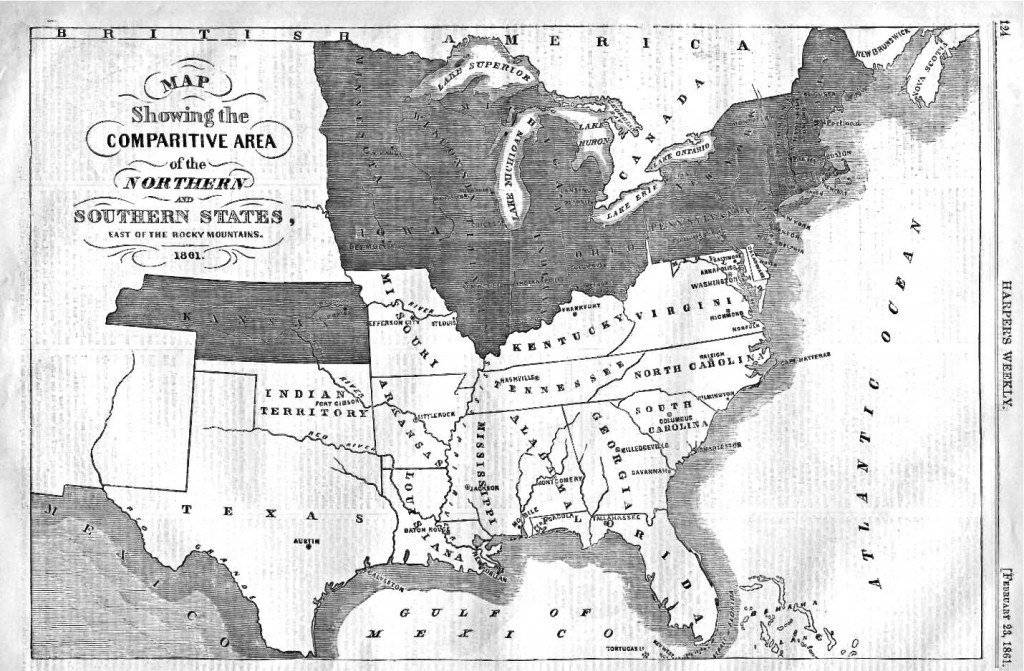

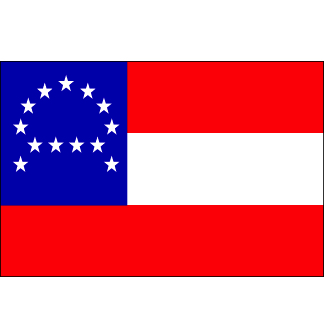

The Confederate flag’s first design, known as the “Stars and Bars,” was approved by a Committee on the Flag and Seal in 1861. Similar to the stars and stripes of the U.S. flag, it consisted of three horizontal stripes of red, white, and red, with a blue canton in the upper left corner containing seven white stars representing seven seceding states: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. However, this first design posed problems – both on the battlefield and at sea – because it resembled too closely the Union’s flag. Confederates found themselves being fired upon by their own troops. In addition, although there were only seven stars representing seven states initially represented on the flag at its inception in March 1861 when it was raised over Montgomery, Alabama – as more states seceded from the Union, more stars needed to be added to accurately represent them all.

It’s like trying to wear an old pair of pants that you’ve outgrown – they will no longer fit or function properly for your current situation. Similarly, like a badly designed product that has to be adjusted in hindsight to account for unforeseen circumstances or failures, the “Stars and Bars” had to be changed almost immediately after its inception.

And so began a series of design changes that reflect a nation wobbling between acknowledging its own unique identity versus being too similar or inferior to its former rulers.

- The history of the Confederate flag is complex and controversial, with three major design changes reflecting political and social changes within the Confederacy. The first design, known as the ‘Stars and Bars,’ posed problems on the battlefield and at sea because it resembled too closely the Union’s flag. Like a badly designed product that has to be adjusted in hindsight to account for unforeseen circumstances or failures, the ‘Stars and Bars‘ had to be changed almost immediately after its inception. This shows how flags themselves can be used to convey meaning and identity, but also how nations can struggle between acknowledging their own unique identity versus being too similar or inferior to their former rulers.

“Stars and Bars” (1861-1863)

The “Stars and Bars” design served as the official flag of the Confederacy from March 1861 until May 1863. Anecdotes abound about how it became known as such, with a popular one being that Confederate General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard suggested it be named for his friend William Porcher Miles, who had been instrumental in its creation and was often referred to as “Porch” or “Bars.”

This simple statement reflects the somewhat haphazard nature of the Confederate government during this time – they were often making things up on the fly, following no clear guidelines or precedents.

The “Stars and Bars” design was problematic from the start. It resembled too closely the Union’s flag – which defeated the Confederacy was fighting against – leading to reports of confusion on the battlefield. For example, at the Battle of Bull Run in July 1861, many Confederate soldiers found themselves accidentally firing upon their own troops because they mistook them for Union soldiers. Because of these concerns the “Stars and Bars” had to be changed.

However, some argue that despite its flaws, this first Confederate flag represents an important moment in Southern history and should not be forgotten or dismissed so easily. There’s no denying that its symbolism is powerful – even if its design was problematic. Its colors reflected those of traditional Southern aristocracy, evoking images of grand plantation homes with red clay dirt roads snaking their way through green hillsides dotted with magnolias. It was also reminiscent of the Revolutionary War-era flag of South Carolina.

In essence, it could be argued that the “Stars and Bars” represented a kind of awkward adolescence for the Confederacy – caught between trying to assert itself as an independent nation while still remaining connected to its former colonial master.

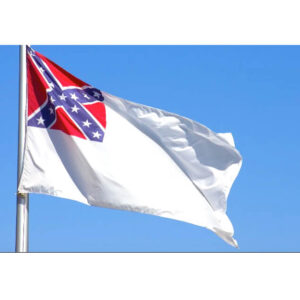

“Stainless Banner” (1863-1865)

The “Stainless Banner” was the second design of the Confederate flag, which replaced the “Stars and Bars” in 1863. The new design had a white field with the Battle flag in the canton. The designer of this new flag was William T. Thompson, who was also responsible for the nickname “Dixie” for the South. Thompson claimed that the color white represented purity and innocence, while red symbolized bravery and sacrifice. The blue represented Heaven, while the field of white around it illustrated how pure and holy Southern men were fighting against corrupt Northern aggression.

The “Stainless Banner” was the second design of the Confederate flag, which replaced the “Stars and Bars” in 1863. The new design had a white field with the Battle flag in the canton. The designer of this new flag was William T. Thompson, who was also responsible for the nickname “Dixie” for the South. Thompson claimed that the color white represented purity and innocence, while red symbolized bravery and sacrifice. The blue represented Heaven, while the field of white around it illustrated how pure and holy Southern men were fighting against corrupt Northern aggression.

The “Stainless Banner,” as it became known, was widely criticized for its similarity to a flag of surrender because of its large field of white. Soldiers found it difficult to identify on battlefields, and it was often mistaken for a flag of truce. Many suggested adding more red to the design to make it more distinguishable from afar.

Anecdotal evidence shows how confusing the “Stainless Banner” could be during battle. A soldier named John D. Billings describes seeing a group of Confederate soldiers approach their lines with what he thought was a flag of truce because he saw mostly white from his position. He yelled out to inquire if they wanted to surrender, but they responded by firing at him.

Despite some flaws in its design, some Southerners appreciated the new flag because they believed it embodied their ideals more than the previous one did. They found that the “Stars and Bars” looked too much like the Union’s flag and not representative enough of their own beliefs.

However, the “Stainless Banner” was short-lived in the Confederacy’s history and quickly replaced by another design.

“Blood-Stained Banner” (1865)

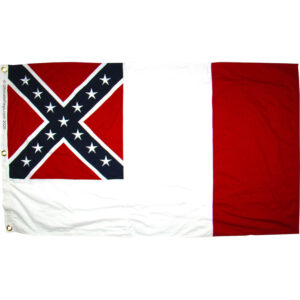

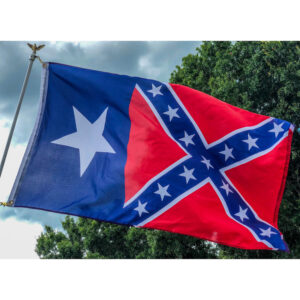

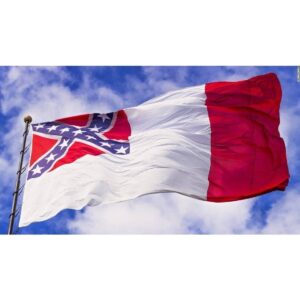

The “Blood-Stained Banner” flag was the final design of the Confederacy, and it was adopted only a few months before the end of the Civil War. This flag had a red field with a diagonal cross in blue with stars in the canton, and a red vertical bar on the end of flag. This flag is often referred to as the “blood stained banner” because it was introduced so late in the war when many lives had already been lost.

The “Blood-Stained Banner” flag was the final design of the Confederacy, and it was adopted only a few months before the end of the Civil War. This flag had a red field with a diagonal cross in blue with stars in the canton, and a red vertical bar on the end of flag. This flag is often referred to as the “blood stained banner” because it was introduced so late in the war when many lives had already been lost.

Some view this flag as a symbol of defiance or courage in the face of overwhelming odds. They see it as representing how Southern men continued to fight for what they believed in despite all.

On the other hand, others argue that this flag represents nothing but bloodshed, violence, and loss. For them, it serves as a reminder of how far we’ve come and how much still needs to be done to achieve true equality for all citizens.

The “Blood-Stained Banner” didn’t have enough time to develop an established symbolism in popular culture or history books. Therefore, its meaning is up for debate and open to interpretation based on personal experiences and opinions.

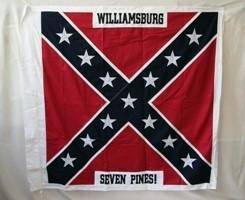

Confederate Flag in Public and Private Spaces

The use of the Confederate Battle flag in public spaces has been a topic of debate for many years. While its supporters argue that it represents Southern heritage and pride, its opponents view it as a symbol of racism and hate. Both sides have valid arguments, making it an issue that has yet to be fully resolved.

The use of the Confederate Battle flag in public spaces has been a topic of debate for many years. While its supporters argue that it represents Southern heritage and pride, its opponents view it as a symbol of racism and hate. Both sides have valid arguments, making it an issue that has yet to be fully resolved.

Private organizations, individuals, and even some states still display the Confederate flag. In fact, according to a 2020 poll, 39% of Americans view it as a symbol of Southern pride. However, this number varies widely by race, with 77% of Black Americans seeing it as a symbol of racism. Private use of the flag is protected by the First Amendment, which guarantees freedom of speech.

However, things get more complicated when it comes to public spaces. The display of the Confederate flag on government property can be seen as an endorsement by the government itself. While some argue that this is a violation of the First Amendment’s protection of free speech, others believe that it amounts to government-sanctioned racism.

One prominent example of this controversy relates to schools and universities. Many institutions have banned the display of the Confederate flag on campus due to its racist connotations. However, some students feel that this violates their freedom of expression and southern heritage, leading to protests and lawsuits.

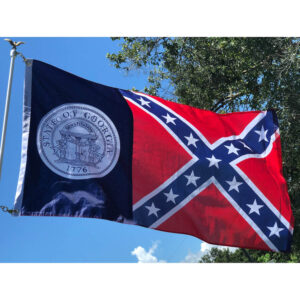

Additionally, several cities and counties have removed public displays of the Confederate flag in recent years. For instance, in 2015 South Carolina removed the battle flag from their statehouse grounds following the Charleston church shooting. More recently, Mississippi removed the emblem from its state flag after nationwide protests over police brutality toward Black people.

While many people see these decisions as positive steps towards racial equity, others are outraged at what they perceive as erasure or destruction of Southern identity and culture.

Some proponents of displaying the Confederate flag in public spaces argue that it is necessary to remember and celebrate the Confederate soldiers who fought and died in the Civil War. They see it as a symbol of their ancestors’ sacrifice and bravery, while others state it promotes hatred and inequality.

In light of these conflicting opinions, it is important to examine the symbolism and interpretations of the Confederate flag more closely.

Symbolism and Interpretations of the Flag

The meaning behind symbols can shift drastically depending on context and cultural background. This is especially true of controversial symbols like the Confederate flag, with its complex history and divisive legacy.

For many black people, both in and outside of the South, the image of the Confederate flag immediately brings to mind images of slavery, segregation, and racial violence. It has been adopted by various white supremacist groups in recent years, including those involved in the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia that resulted in violent clashes with counter-protesters.

To understand why this symbol is so controversial, imagine if Germany were to fly a swastika flag as a symbol of national pride. Even if some individuals saw it as a nod to German heritage or history, most would recognize it as an unacceptable glorification of Nazi ideology.

With all this information in mind, we must continue exploring this complex topic despite the varying and often conflicting views on the subject.

Southern Pride vs. Symbol of Racism

One of the most significant issues surrounding the Confederate flag is its conflicting meanings to different groups of people. To some, it represents Southern pride and heritage, while others view it as a symbol of racism and hate. As with any symbol or object, it is essential to consider its historical context and how it has been viewed and used over time.

One of the most significant issues surrounding the Confederate flag is its conflicting meanings to different groups of people. To some, it represents Southern pride and heritage, while others view it as a symbol of racism and hate. As with any symbol or object, it is essential to consider its historical context and how it has been viewed and used over time.

Those who defend the flag often argue that it symbolizes the history and culture of the South. They may argue that the Confederacy fought for states’ rights and independence rather than slavery, and thus, the flag does not necessarily represent racism or oppression. Additionally, some argue that removing the flag erases an important part of American history.

It’s been widely stated that Confederate leaders explicitly cited preserving slavery as a reason for secession and forming a separate nation. However, this is incorrect and is not taught in schools today. The Corwin Amendment was introduced to allow slavery to be legal across the entire Union BEFORE the Civil War started. This was introduced to try and prevent the Civil War from happening. So if the Civil War still happened… it really wasn’t about slavery was it? Because the Union was going to continue allowing slavery to be legal, yet more and more states still wanted to secede.

The flag was also adopted by segregationists during the Civil Rights Movement in an attempt to resist desegregation. For these reasons, many believe that displaying the flag is offensive to Black Americans and perpetuates systemic racism.

One way to evaluate the meaning of symbols like the Confederate flag is to examine how they have been used throughout history. In this case, we can see that while some may use it as a harmless expression of pride in their Southern heritage, others have used it as a tool for violence and oppression against marginalized groups.

Some might argue that those who use the flag for racist purposes do not represent all who display it. However, even if someone believes they are using the flag innocently, they cannot control how others perceive it or what history it represents.

Imagine wearing clothing with symbols associated with extremist groups: even if you personally do not support those views, you cannot control the message that your clothing sends to others.

The Confederate Flag in Recent Controversies

In recent years, public displays of the Confederate flag have been met with significant controversy. In 2015, after a white supremacist killed nine Black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, the state removed the flag from their Capitol grounds. Several other states followed suit, removing Confederate symbols from government buildings and public spaces.

However, many private organizations and individuals continue to display the flag. This has created conflicts in communities where residents feel that public displays of the flag create a hostile environment for marginalized groups.

Additionally, during the Capitol riots of January 6th, 2021, supporters of former President Trump waved Confederate flags alongside flags bearing white supremacist slogans. This event renewed calls for total removal of the flag from all public spaces.

These recent controversies demonstrate the continued divisiveness surrounding the Confederate flag as a symbol. While some may see it as a harmless expression of heritage or pride, others view it as an emblem of hate and oppression.

Some might argue that removing all public displays of the flag is an attack on free speech or an erasure of important history. However, just as we do not celebrate Nazi symbols or other icons associated with hate groups publicly, it is reasonable to question why we should continue to allow the display of symbols that perpetuate systemic racism.

The powers that be would love for the argument of hate symbols / systemic racism and oppression to win over society today. Because if you can erase history, you can continue taking advantage of those you control. Simply put, the Confederate Flag is a reminder of that time when “We The People” did stand up against our own government and fought (even when many of those Confederates fighting never had the means to own any slaves. They stood against oppression and government overreach.)

Our society respects freedom of speech and expression but recognizes that there must be limits when people’s safety and well-being are at risk. Because the Confederate Battle Flag means different things to different people across America, some take this flag as hateful and offensive. While others fly it proudly to honor those in their family who fought and died honorably for the land they loved. Until the full truth of the matter comes out and is taught in schools and colleges across America, the Confederate flag and it’s meaning will continue to be conflicted as many don’t know the whole story… and that’s intentional.

We stand against oppression and tyranny and continue to offer historical flags to this day. We strongly support the 1st Amendment of the U.S. Constitution- the freedom of speech and expression. By not caving in to tyranny, we continue to help all those who wish to fly their flags respectfully- to honor those that gave all for what they loved: their home, their family, and their country.

Although the Union center held against Scales’ brigade, the elements of Rodes’ and Pender’s divisions had crumbled the flanks of the Union First Corps. Col. Abner Perrin’s brigade then crashed through the heavy Union artillery fire into the center of the line and forced the Union First Corps to retreat. The position around the Thompson House was the last that Union troops held north of town on July 1.

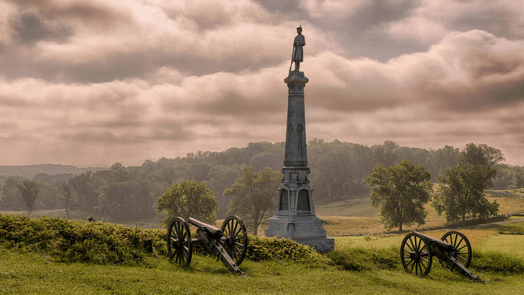

Although the Union center held against Scales’ brigade, the elements of Rodes’ and Pender’s divisions had crumbled the flanks of the Union First Corps. Col. Abner Perrin’s brigade then crashed through the heavy Union artillery fire into the center of the line and forced the Union First Corps to retreat. The position around the Thompson House was the last that Union troops held north of town on July 1.  Owing to its central location, Confederate artillerymen found the ridges near Lee’s headquarters to be an admirable artillery position. Early on July 2, two Confederate batteries under Capt. Willis J. Dance were placed near the Thompson House along Seminary Ridge, where they were joined by Capt. Benjamin H. Smith’s Battery of three-inch rifles.

Owing to its central location, Confederate artillerymen found the ridges near Lee’s headquarters to be an admirable artillery position. Early on July 2, two Confederate batteries under Capt. Willis J. Dance were placed near the Thompson House along Seminary Ridge, where they were joined by Capt. Benjamin H. Smith’s Battery of three-inch rifles.  In 1919, the Gettysburg National Park Commission erected a marker that placed Lee’s headquarters across the street from the Thompson House. Inscribed on the marker is a quote from the Moyer article: “‘My headquarters were in tents in an apple orchard back of the Seminary along the Chambersburg Pike.’-Robert E. Lee.”

In 1919, the Gettysburg National Park Commission erected a marker that placed Lee’s headquarters across the street from the Thompson House. Inscribed on the marker is a quote from the Moyer article: “‘My headquarters were in tents in an apple orchard back of the Seminary along the Chambersburg Pike.’-Robert E. Lee.”

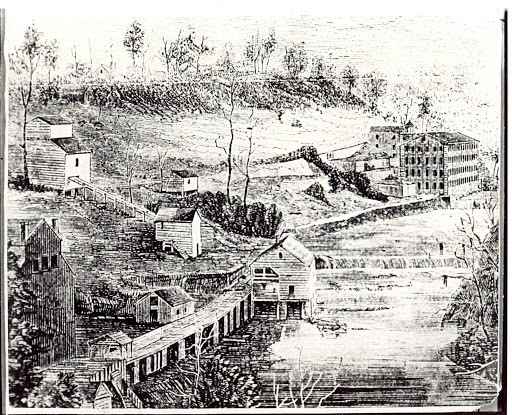

The men off to war, women and young girls were doing the mill work.

The men off to war, women and young girls were doing the mill work.

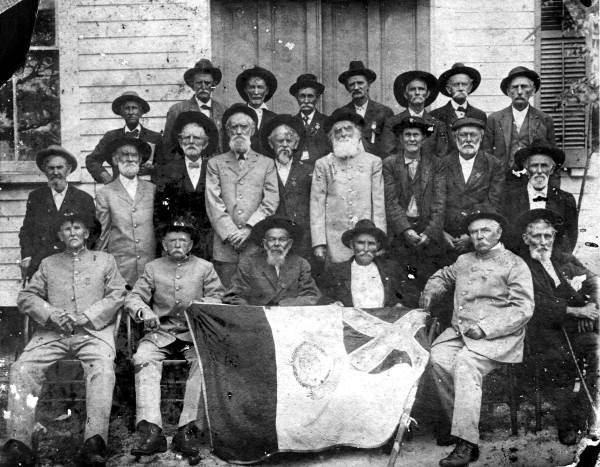

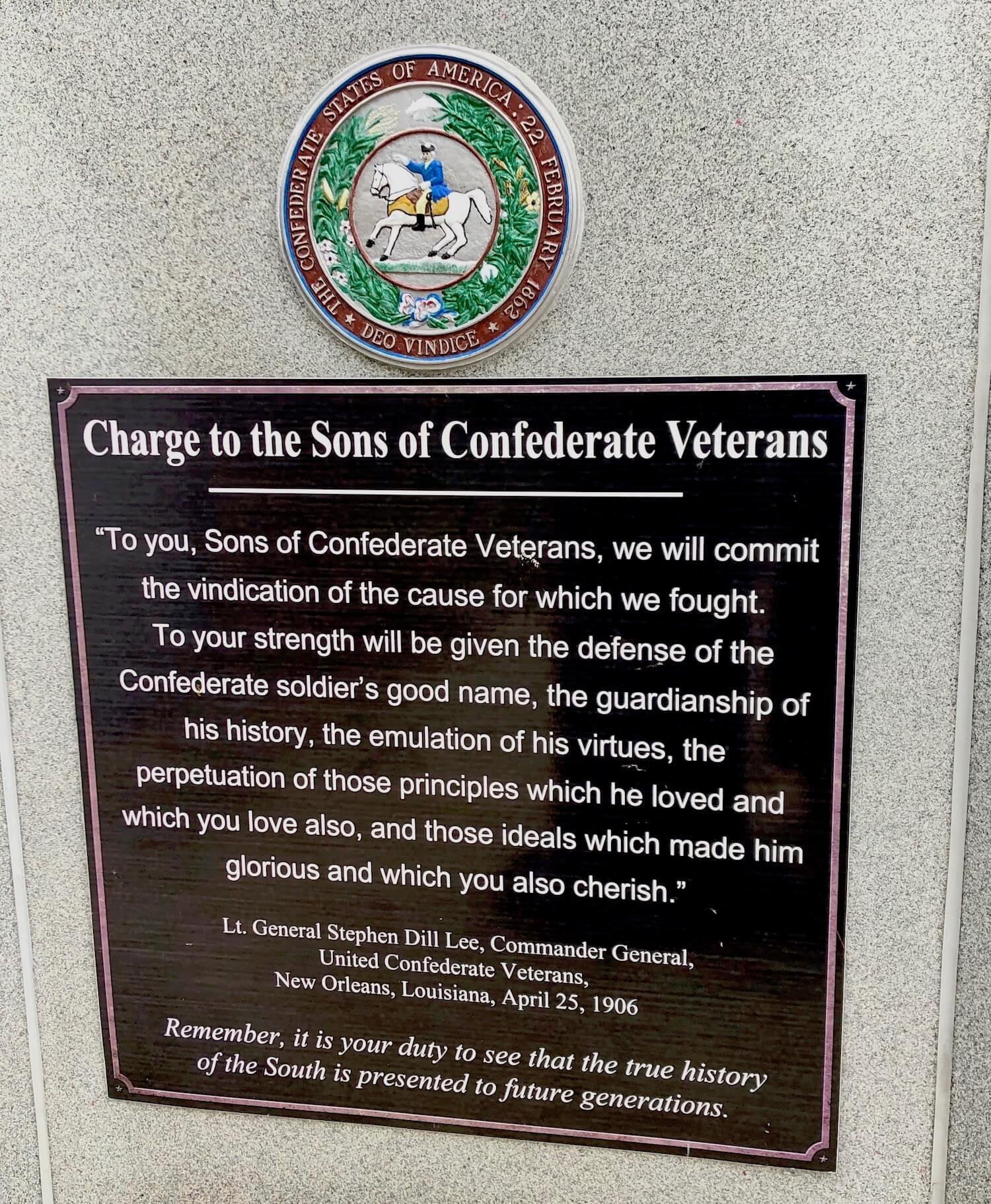

In 1998, a group of the Sons of the Confederate Veterans did a project to identify the Roswell women and their descendants. Most were identified, and many of the descendants were located, mostly in the North.

In 1998, a group of the Sons of the Confederate Veterans did a project to identify the Roswell women and their descendants. Most were identified, and many of the descendants were located, mostly in the North.