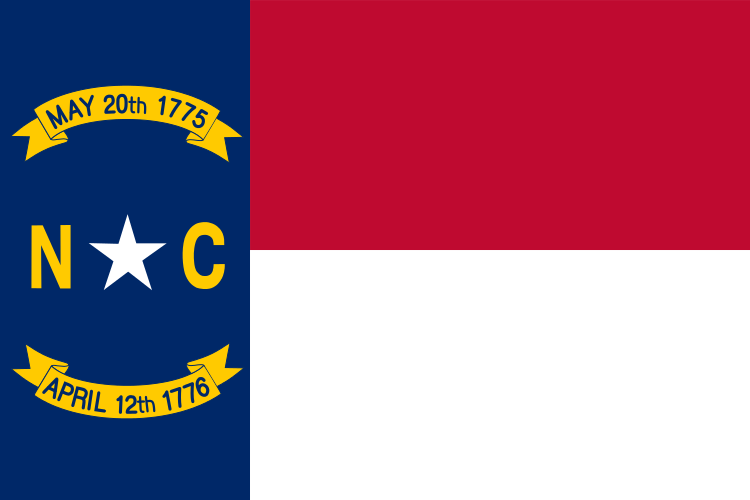

If you have been following this search then you know that in Part II the evidence began to point to a lone star on a blue field as being the Confederate flag of Alabama at secession. In this final segment we will see what this flag actually looked like.

The turbulent times of 1860-1861 called for political messages to be sent by the man on the street, and many flags were being flown. For example, the following is taken from an article in the December 22nd, 1860 edition of the Utah Territory newspaper, “The Mountaineer”:

“The principal flag being shipped to Alabama is one modeled after our national bunting, but having fifteen stripes and fifteen stars in a blue field, encircling the words: “A united South.”

No one, though, would imagine this was a candidate for the new state flag.

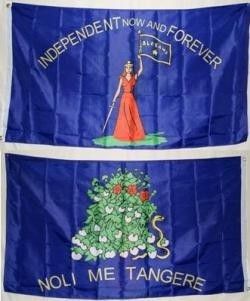

Alabama Republic Flag

On the other hand, we know that flags with a single star did fly over Alabama after secession; indeed, in many areas of the South: it was a popular image (more on that in a moment). And as covered in Part II, we have Lady Liberty on the secession convention banner holding a flag with a blue field and a single star below the letters “ALABAMA.” Do we have anything else that makes us thing this was the pattern of Alabama’s flag at this time?

Yes, but let me provide a quick background to it. To do this we have go back into some very ancient history for a moment.

PLEIADES: THE SEVEN SISTERS

The Pleiades is a constellation of stars that is visible from virtually everywhere humans live. It is often called the Seven Sisters in the Western World. These were the seven daughters of the Greek God Atlas and the sea spirit Pleione. (Atlas is the god who holds the world on his shoulder.)

This collection of stars has been known for a long time. We find them in Chinese writings from over 3000 years ago. The ancient Greek Poet Hesiod mentions them in a poem written around 700 BC, and Homer speaks of them in the Iliad and Odyssey. The Bible contains at least three references to the Pleiades, in Job 9:9 and 38:31, and Amos 5:8.

However, one of these stars is less bright than the others, and at night most people can only see six of them. The story of a lost seventh Pleiad (sister), is a universal theme on Earth. We find the lost Pleaid myth in European, African, Asian, Native American and Aboriginal Australian lore.

“THE LOST PLEIAD FOUND”

Earlier in this story we saw how delegate William Smith kept a journal on the Alabama Secession Convention. He concluded the journal with a poem, entitled “The Lost Pleiad Found.” Here it is:

“Long years ago, at night, a female starFled from amid the Spheres, and through the spaceOf Ether, onward, in a flaming car,Held, furious, headlong, her impetuous race:She burnt her way through skies; the azure hazeOf Heaven assumed new colors in her blaze;Sparklets, emitted from her golden hair,Diffused rich tones through the resounding air;The neighboring stars stood mute, and wondered whenThe erring Sister would return again:Through Ages still they wondered in dismay;But now, behold, careering on her way,The long-lost PLEIAD! lo! she takes her placeOn ALABAMA’S FLAG, and lifts her RADIANT FACE!”

A lone star, in an azure sky, Alabama’s proud Confederate flag. Azure being a bright blue, we know the flag was gold and blue, as depicted in the flag in Liberty’s hand in the Alabama Secession Flag.

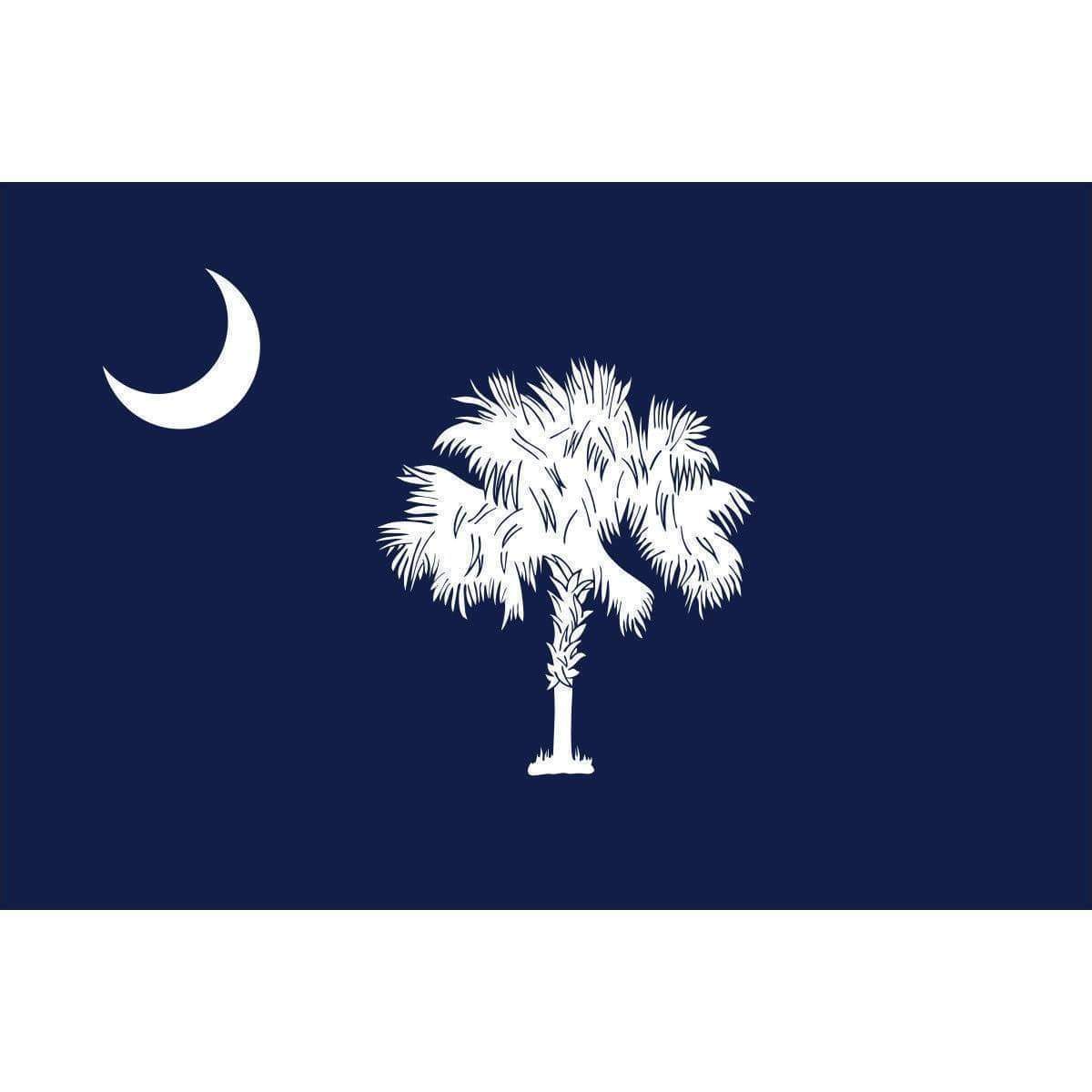

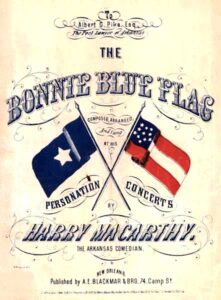

This basic pattern was a familiar to Southerners. It has taken on various forms, including that of the Bonnie Blue Flag.

The Bonnie Blue has a white star on a blue background. It is the first recorded use of a lone star flag in the South, and dates to 1810. At that time there was a Spanish province called West Florida, made up of parts of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. West Florida declared its independence from Spain in September of 1810, and became part of the U.S. one month later. Carrying a blue flag with a single, five-pointed star, citizen forces captured Baton Rouge without loss to themselves, and imprisoned the Spanish governor.

The Bonnie Blue has a white star on a blue background. It is the first recorded use of a lone star flag in the South, and dates to 1810. At that time there was a Spanish province called West Florida, made up of parts of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. West Florida declared its independence from Spain in September of 1810, and became part of the U.S. one month later. Carrying a blue flag with a single, five-pointed star, citizen forces captured Baton Rouge without loss to themselves, and imprisoned the Spanish governor.

The Bonnie Blue flag was well known to the populations in or near the old territory of West Florida, including Alabama, and was to become a popular rebel flag.

In early 1861, the Bonnie Blue flew over the capital building in Jackson, Mississippi, inspiring the southern patriotic song – “The Bonnie Blue Flag,” composed by Harry McCarthy. From what we can tell, this song was almost as popular as “Dixie” among Southern troops. Here is the first verse of that song:

We are a band of brothersAnd native to the soil,Fighting for the propertyWe gained by honest toil;And when our rights were threatened,The cry rose near and far–“Hurrah for the Bonnie Blue FlagThat bears a single star!”

A chorus of the song speaks of the first states to secede:

First gallant South Carolina

nobly made the stand

Then came Alabama

and took her by the hand.

Next, quickly Mississippi, Georgia, and Florida

All raised on high the Bonnie Blue Flag

that bears a single star.

There is no doubt that the Bonnie Blue was flying in many locations in Alabama at the time of secession, as it was in other Southern states. We can see how Alabama might have adopted the Bonnie Blue, but in what form?

We have indications that Alabama was using a yellow or gold star, not a white one. One of these clues is the color of the star on the Alabama Republic flag above, which appears to have been yellow or gold. This color is also suggested by Smith’s use of the lost Pleiad’s “golden hair” in his sonnet about the flag. The Seven Sisters of Greek mythology are traditionally portrayed with darker hair, in keeping with their Mediterranean heritage.

The likely design of the Confederate Flag of Alabama at secession, the Alabama flag of independence, had a single golden star on a blue field. We can be sure that the shades of color and dimensions of the flag widely varied, as certainly did the star’s size. But the basic appearance would have been as described above.

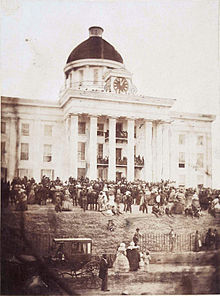

The Convention itself had an official status, and the members of the Convention knew what the Alabama flag was. Had we been standing in the streets of Montgomery on the 11th of January, 1861, we would have seen flags with a lone star on a blue field – or been waving them ourselves. This was the accepted flag of Alabama at the time of secession, regardless of its unofficial status in the eyes of our modern authorities.

Thanks for reading. Please share our posts with your friends and family so they too can learn more about Southern Heritage and History.

Brought to you by: Ultimate Flags