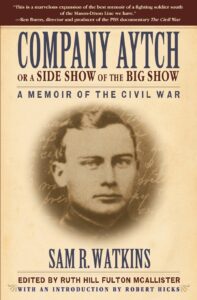

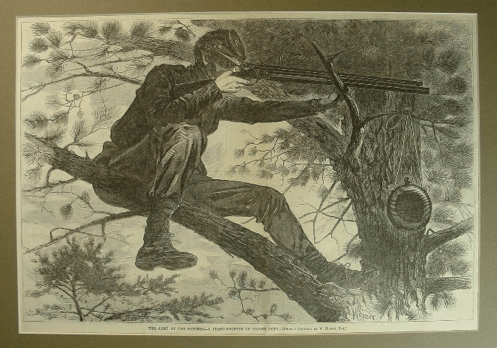

The 1st Tennessee Regiment was camped near Corinth, Mississippi. The men of Company H were getting tired of being shot at, and losing their buddies. Private Sam Watson explained, “…our men were being picked off by sharpshooters, and a great many were killed.

No one could tell where the shots were coming from, but at one post “it was sure death.” For the past week, everyone, without exception, sent to that post had been killed. Then Sam got some bad news:

“In distributing the detail this post fell to Tom Webb and myself. They were bringing off a dead boy just as we went on duty.”

But a soldier doesn’t get much say about these things, so Sam and Tom took their posts. Sam writes,

“A minnie ball whistled right by my head. I don’t think it missed me an eighth of an inch. Tom had sat down on an old chunk of wood, and just as he took his seat, zip! a ball took the chunk of wood. Tom picked it up and began laughing at our tight place.”

Sam glanced toward some tree tops and saw smoke rising above a tree, and noted:

“and about the same time I saw a Yankee peep from behind the tree, up among the bushes.”

Watson pointed Tom to the spot. They could see the Yankee was loading his gun, the ramrod sticking out from behind the tree. I’ll let Sam tell you what happened:

“…both of us had dead aim at the place where the Yankee was. Finally we saw him sort o’ peep round the tree, and we moved about a little so that he might see us, and as we did so, the Yankee stepped out in full view, and bang, bang! Tom and I had both shot. We saw that Yankee tumble out like a squirrel… One thing I am certain of, and that is, not another Yankee went up that tree that day.”

Thanks for reading. Please share our posts with your friends and family so they too can learn more about Southern Heritage and History.

Brought to you by: Ultimate Flags