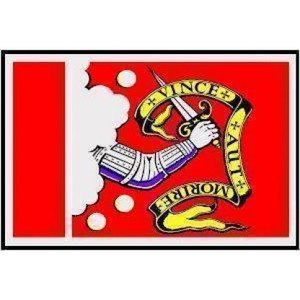

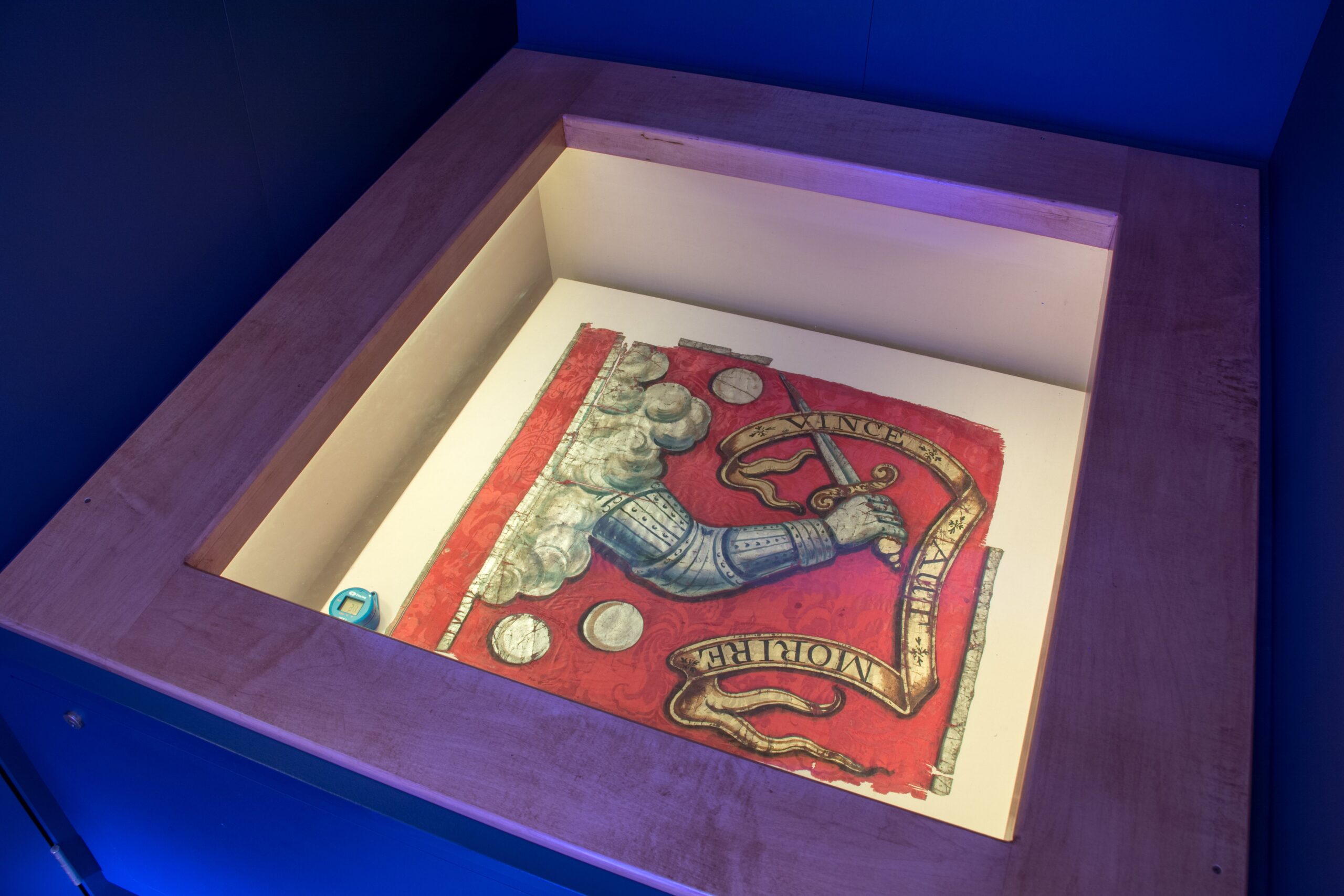

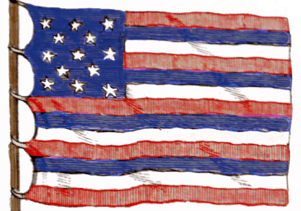

Betsy Ross made flags for 50 years, and we are all familiar with the famous circular 13-star design. Fewer know about Francis Hopkinson, signer of the Declaration of Independence and designer of our Stars and Stripes. Letters between Hopkinson and the Continental Congress tell the story, and these letters can be found in the National Archives. In 1780 Hopkinson was the Treasurer of the Continental Loan Office. He also consulted with a committee to design the Great Seal of the United States. We have a letter he wrote to the committee, with a proposed design for the seal. In that letter, he also wrote about having designed the American flag in 1777. Since he was a public servant, his design was free, what he called “Labours of Fancy.” He did suggest, however, that receiving a “Quarter cask of the public wine” would be a nice show of appreciation. (This was thought a reasonable request, but by the time it made its way through the red tape of the government, it was never approved and Hopkinson never got his cask of wine.)The Continental Congress had in fact adopted our flag in July of 1777, a design described and provided by the Marine Committee. Hopkinson had served as the chairman of a board under that committee.While no flags have survived from that period, and we don’t have the original drawing, we do have a sketch likely done by Hopkinson that shows the linear pattern of the stars. It is that pattern that we proudly fly today as the Hopkinson Flag.

Thanks for reading! We hope you enjoyed our post. Please share with all your fellow patriots. Brought to you by: Ultimate Flags