Late Spring 1864: Grant wanted to take the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. He had been trying to slip around the Rebels, but the wily Lee kept blocking him.

Now Grant made a wide swing to flank the Rebels and seize Cold Harbor.

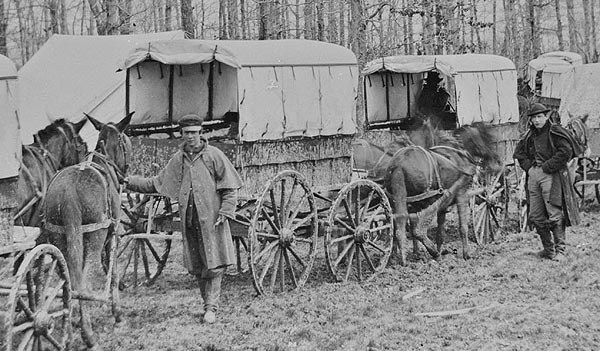

Not a real town, Cold Harbor was just an intersection of roads, ten miles northeast of Richmond. It got its name because of a tavern where guests could “harbor,” but no hot food was offered. You can see the inn in the photo below, taken on the 4th of June, 1864.

Grant arrived, but again Lee had beat him to the punch.

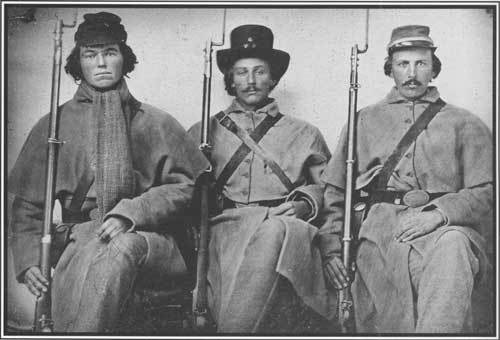

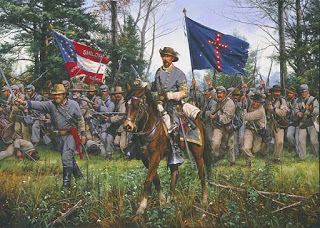

No one was better at building fortifications than Uncle Billy and his battle-hardened Rebels. In just days, they had built six miles of artillery emplacements, trenches and fortifications.

Now Grant made a crucial mistake: he thought Lee’s army was on the ropes, “really whipped.” Nothing could be further from the truth, as he was about to discover.

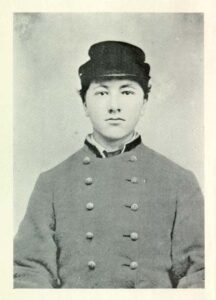

An all-out attack was ordered for the next day. That night Union Lieutenant Colonel Porter watched men writing their names on paper and pinning them inside their uniforms. The privates knew better than their commander what was in store.

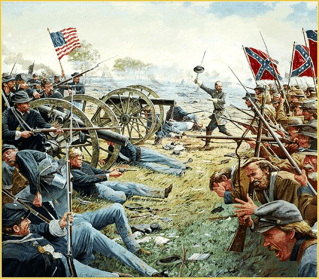

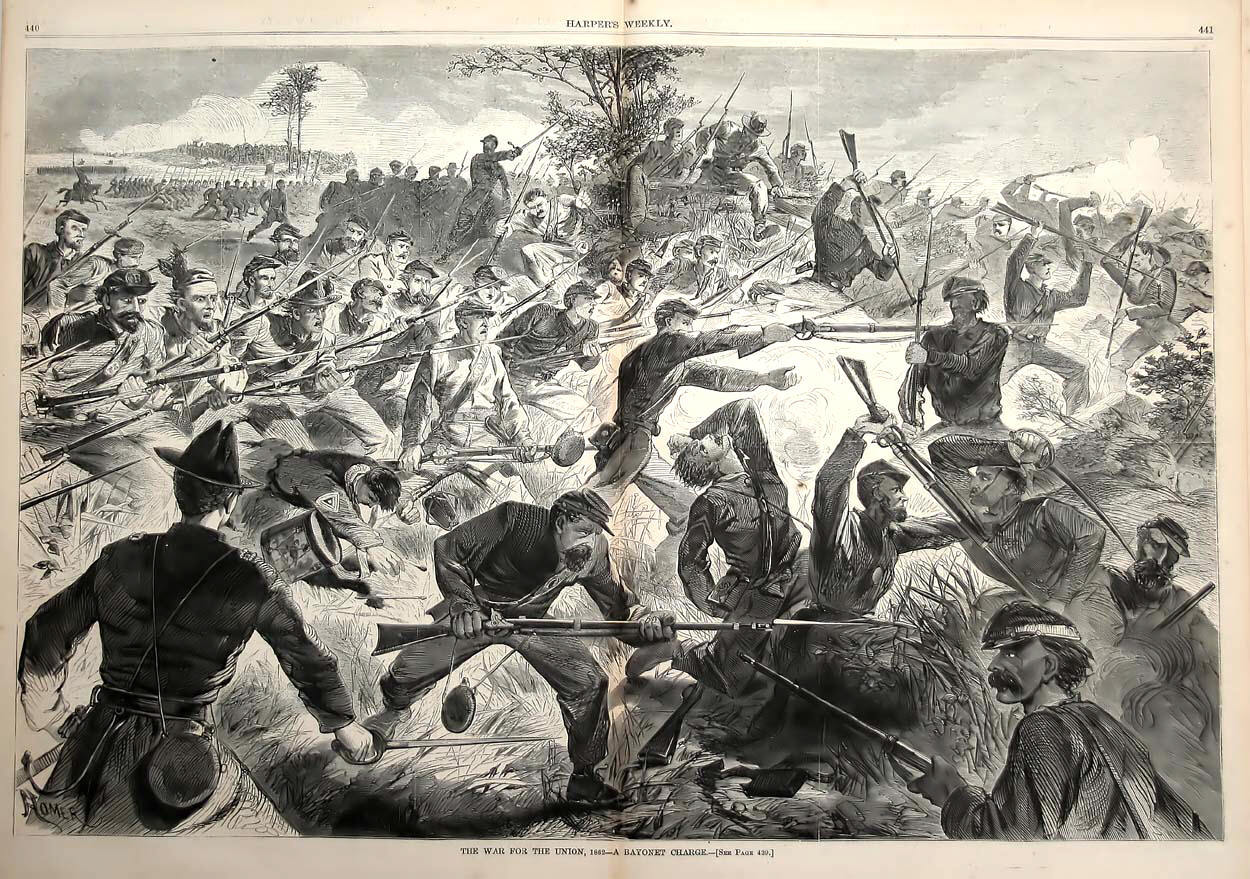

The Federals advanced at 4:30 AM, through thick fog. Confederate cannon and rifle fire soon had most of them pinned down.

One of Yankees described the assaults as “a wild chain of doomed charges, most of which were smashed in five or ten minutes.”

Another later wrote, “We felt it was murder, not war…”

Another later wrote, “We felt it was murder, not war…”

One man saw all of the men around him suddenly drop to the ground. Assuming orders had been given, he dropped too. It was only then he realized the other men were dead.

In the span of one hour, 7,000 Union men were killed or wounded. No other hour of the war saw such a loss. By 7 AM, it was obvious to the Federals on the field that the attack was hopeless. When Union Major General Smith received orders for his 16,000 men to advance further, he refused, calling it a “wanton waste of life.”

When the assault was called off, many of the Union men could not retreat for fear of being killed. They had to somehow dig in where they were, creating what protection they could.

The difference in casualties was staggering. A Union army of 108,000 had been stopped in their tracks: 1,844 dead, 9,077 wounded, 1,816 captured or missing.

The 62,000 men of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia suffered 83 dead, 3,380 wounded, 1,132 captured or missing.

The Union army remained for nine more days, the front lines sometimes only yards apart.

It was a mistake Grant remembered for the rest of his life: “I regret this assault more than any one I have ever ordered.”

Thanks for reading. Please share our posts with your friends and family so they too can learn more about Southern Heritage and History.

Brought to you by: Ultimate Flags

A Federal officer rode up and hollered, “We have whipped them on all points.”

A Federal officer rode up and hollered, “We have whipped them on all points.” A Confederate shell destroyed the buggy of Senator Henry Wilson, and he had to escape on a mule. Iowa Senator James Grimes barely avoided capture (and swore he would never go near another battlefield).

A Confederate shell destroyed the buggy of Senator Henry Wilson, and he had to escape on a mule. Iowa Senator James Grimes barely avoided capture (and swore he would never go near another battlefield).